Metropolis

by: Terry Matthew

In Defense of the Machines: A New Look at the Future World of Metropolis

Held overnight as authorities combed through his papers, Fritz Lang climbed onto the deck of a ship moored in New York Harbor and gazed in awe at the horizon. His visa problems weren't cause for alarm; this wasn't even the director’s first time being held as an "enemy alien." He'd be released and allowed to disembark from the SS Deutschland when things were straightened out the next day.

But it was here — with his feet on a ship called "Germany" and his gaze fixed on the Manhattan skyline — that Lang had a vision for his next movie, a kind of film that had never been made before.

"I saw a street lit as if in full daylight by neon lights," he would later say. "Topping them [were] oversized luminous advertisements, turning, flashing on and off, spiraling... something which was completely new and nearly fairy-tale-like for a European in those days...

"The buildings seems to be a vertical veil, shimmering, almost weightless, a luxurious cloth hung from the dark sky to dazzle, distract and hypnotize. At night the city did not give the impression of being alive: it lived as illusions lived." [1]

"There," Lang would later tell director Peter Bogdanovich, "I conceived Metropolis."

This story is not entirely true. There's ample evidence that preparations for Metropolis were underway — including the script being written by his then-wife Thea von Harbou — before Lang and producer Erich Pommer of German studio giant UFA boarded the SS Deutschland in 1924. But Lang, a master of semiotics, recognized a good symbol when he saw one. This fable — one which memorialized his groundbreaking film as both German and international at once — became the foundational myth behind the making of Metropolis.

Yet there's no question that the electric cathedrals of New York City really inspired the shocking visuals of Metropolis, as did the Americans he met when the two Germans wandered the city the next day. It was "dreadfully hot," Lang recalled, a maelstrom of humanity like a "crater of blind, confused human forces — pushing together and grinding upon each other."

Multiple books have been written about what inspired Lang and Metropolis, the references to visual art, paintings and the tribal masks that inspired the face of the Maschinenmensch, the film's iconic android. But why does Metropolis continue to inspire us? What is it about this silent film, its message and its themes, that has moved some of our most celebrated musicians to set it to music? And why are so many electronic music composers in particular fascinated by a film about the future that's more than 100 years old?

Metropolis was dismissed as a "fairy tale" by more than one critic in its day. It was not a popular success when it was released, and it would have been difficult for the film to make its gigantic budget back anyway. Some criticized what they identified as a "communistic" message in its plot, a warning of what could happen when workers driven into the ground rise up against the ruling class. German sociologist, writer and critic Siegfried Kracauer argued it captured proto-fascist ideals that were congealing beneath the firmament of German society at the time.[2] Drama critics dismissed the story as simple, "puerile," almost embarrassing.

Movie executives saw it as a catastrophe, and would cut more than 1/4th of the film after its German premiere. Nazis hacked away even more. Once judged the most expensive film ever made, everyone had an idea where Lang went wrong.

But as Metropolis was pieced back together over the last century — reassembled from scattered prints and the notes of a Nazi censor — the scope of Fritz Lang's vision became clear. Metropolis has undergone a critical reappraisal and is today regarded as one of the greatest films ever made — Sight and Sound’s influential poll last tracked it at #35, tied with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. [3] And in many ways, it is these “flaws” picked at by critics in 1927 that gives the film its power to break through to audiences that would never otherwise watch a silent film. In Metropolis, Lang and von Harbou construct a new mythology in the shell of the old — one that can be told simply and understood by children, and also interpreted, analyzed and ruminated over by scholars and wise men in search of meaning.

What If One Day Those in the Depths Rise Up Against You?

Metropolis takes place in an eponymously named city at some point in the future (the years 2000, 2026 and 3000 have all been referenced by various entities connected with the movie over the years). Society has become intensely stratified, the elites of the city living decadent lives at the top of gigantic art deco skyscrapers. The workers, on the other hand, trudge robotically from factories to their homes in an underground city. Health, fresh air and seemingly even happiness are a privilege of a well-born elite.

Freder, son of the ruler of Metropolis, is about to have his way with a hand-selected courtesan when a woman, Maria, breaches the Eternal Garden with a handful of mendicant children from underground. Their sunken eyes gaze around as she gestures at the glamorous people. "Look," she says to the children, "these are your brothers."

These are the words that ignite the plot and propels Metropolis to destruction and redemption. A shaken Freder stumbles after Maria, only to witness an industrial accident which kills several workers. In the aftermath, he hallucinates the gigantic factory transformed into Moloch, god of human sacrifice, devouring workers as "living food for the machines."

Freder runs to tell his father, Joh Fredersen, what happened. Fredersen didn't know, and Freder is naïve enough to believe that his father might care about it as a human tragedy rather than a financial one.

This scene features some of the most important dialog in Metropolis. An audience in 1927 certainly knew this type of villainous industrialist, as well as the dangers of death or disfigurement of employment in the factories and the mines.

"What if one day those in the depths rise up against you?" Freder asks his father. Freder is that boundlessly optimistic youth who can't imagine these conditions exist by design, because it's more profitable to treat workers as disposable tools, less valuable than the machines they serve. Fredersen merely smiles.

"Where are the people, father, whose hands built your city?" Freder asks, in a question that hangs across decades and soon to be centuries of social conflict. One can almost imagine these words being said again, in 2022, in relation to the struggle against systemic racism by the descendants of African slaves. Where indeed are the people whose bodies were broken to build our cities?

None of our leaders answer us, as they do not possess the brutal frankness of the ruler of Metropolis. He answers: "Where they belong."

Death to the Machines

Leaving his father, Freder pursues Maria using a map found with one of the dead, leading him underground to catacombs beneath the worker's city. There, on a pulpit of primitive crosses, Maria speaks to the exhausted workers about a coming messiah — a "mediator" who will bring together the hands (the workers) and the head (the ruling class) of the city. She retells the parable of the Tower of Babel as a story of class struggle — people enslaved to build a monument to mankind ascending as a god, dedicated to "humanity," even while being deprived of their own.

The workers bow their heads. These are the same poor workers Upton Sinclair wrote about in The Jungle, decades before Metropolis was made, which described "the breaking of human hearts by a system which exploits the labor of men and women."

But while the workers practice their religion with Maria, the rulers of Metropolis have their own creed. Fredersen spies on this meeting alongside Rotwang, archetype of the mad scientist but also a sort of magician Fredersen visits when his experts fail him. Rotwang is also a connection between the two castes of Metropolis, but uses it not to mediate between them but to forward his plans for revenge. Rotwang has built a massive sculpture memorializing the face of Hel, his lost love who left him for Fredersen and gave birth to Freder before she died. He's built an android in her image — the Maschinenmensch or Machine-Person. During its construction he's lost a hand and replaced it with a mechanical prosthetic covered in a black glove. Fredersen would like to use the Maschinenmensch to subvert and provoke the workers in order to destroy them. Rotwang plans to use it to destroy the city and thus Fredersen. He's the only human character in the film who is part machine, and he's built another machine in order to destroy the machines.

Metropolis is — superficially — a movie about people vs. machines. But it's important to note that Lang and von Harbou do not at any point portray the machines of Metropolis as "evil." Unlike the vast majority of dystopian films produced in its wake (and many of those directly influenced by it), the machines of Metropolis are just tools. There's no surveillance tech to be found in the film, no torture devices, no malignant computers murdering people with cold calculating logic. People, however, are doing those things. Contrary to Freder's vision, the machines of Metropolis are not Moloch. It’s people that are pushing other people into their jaws of death. During his time undercover, Freder works a punishing 10 hour shift — a schedule which is deliberately set by his father, who has a special 10 hour clock dominating his office wall while his own wristwatch tells time in the normal fashion.

Similarly, the Maschinenmensch is a terrorist but only because it is in the hands of terrorists; it's only doing what it's told. It calls on the workers to revolt not by attacking the ruling class of Metropolis but demanding "Death to the machines!" From its instructions from Rotwang, it seems to understand that attacking a member of the ruling class like Fredersen would merely lead to someone else, possibly worse but certainly no better, leading Metropolis. Attacking the machines, however, would ensure everyone's destruction.

Riled up by the Maschinenmensch, the workers abandon their children to wreck havoc in Metropolis. Only later do they realize that one of those machines they've "killed" — the Heart Machine — is sustaining their underground homes. As rushing and rising flood waters tear apart their city, Maria uses another machine — a giant bell in the city square — for a positive purpose, rallying the abandoned children to lead them to safety.

Metropolis isn't a story of technology escaping from the control of men. It's about technology very firmly in the control of men — heartless men severed from all morality. This is the meaning behind the film's epigram — that the mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart — and one of the reasons the film's message has continued to endure. It's never been about overthrowing the robots or the machines. It's about the people controlling them, how we sense of solidarity and how we can get it back again.

Let's Watch As the World Goes to the Devil

Metropolis was not the only classic film to be butchered upon release, but it may be the most successful case of a classic film being sewn back together again. UFA's American distributors, Parufamet (a joint enterprise between Paramount and MGM) ordered significant cuts. American author Channing Pollock was hired to edit it into a "new" story assembled from the existing footage. Pollock, known today solely for a pithy review from Dorothy Parker (his play The House Beautiful is "the play lousy," she wrote) removed at least 37 minutes from Metropolis for American release. In Germany, Alfred Hugenberg, industrialist and media mogul who had purchased UFA, aimed his cut of the original print at the film’s supposed political subtext. A future member of Adolf Hitler's first cabinet, Hugenberg aimed to purge UFA of the "republicans, Jews and internationalists" at the studio. After the Nazis took power, Metropolis was cut even more, down to 91 minutes. This cut was the version most commonly seen prior to the 1980s (though the preserved notes of the censor aided its eventual reconstruction).

By all accounts, the cuts didn't enhance the film’s reception at the time. The reviews, as mentioned, were fairly bleak. Yet many of the critics who lambasted Lang and von Harbou had a grudging respect for the dazzling visual sights of the film. Critic Thomas Elsaesser reports the reviewer for France's Les Annales attacked the film's "ponderousness," its "pretension" and its "unsurpassable stupidity," while still finding Lang "capable of extraordinary images and imagination." Likewise, filmmaker Luis Buñuel bashed the film for its trivial, pretentious (again), pedantic "hackneyed romanticism." He also thought it could "overwhelm us as the most marvelous picture book imaginable." [4]

But Lang didn't simply dress his sets in neon and chrome. One of the secrets of the film's staying power, strangely, is due to how little "future tech" there is on screen. With the (very notable) exception of the Maschinenmensch, nearly all of the technology of Metropolis is vintage 1920s material. Fredersen and Rotwang walk the catacombs guided by small hand flashlights. Fredersen's sinister henchman, The Thin Man, pulls a phone out of a panel in the backseat of a car. That was probably crazy stuff in the 1920s, but time has been fortunate enough to make it real. There are very few other blind steps into the future in Metropolis. The cars are Model Ts. Biplanes buzz through the city’s steel corridors. The heavy machinery looks like heavy machinery. No one is wearing aluminum foil hats or reflective uniforms or shooting laser guns.

Critics claimed that Metropolis "pretended to be about the future” without making any definitive predictions, Elsaesser writes. However, nothing ages more quickly than "imagined futures" that never happen. Modern viewers are likely more accepting of the biplanes and 1920s fashions and imagining the rest than they would be of kitsch space suits and streamlined jet cars from a future that never came. One of the reasons the film is so modern a hundred years after it was made is because it feels like you can touch Metropolis. The city and its sets feels solid, like you can scratch at it without the cardboard caving in or the foil peeling away.

Many Now Go to the City of the Dead

Even in a truncated form, Metropolis continued to inspire generations of filmmakers and artists but especially musicians. Many watched the film in silence or with unrelated musical accompaniment. An original score was written but most never heard it, as it wouldn't have matched up with the bowdlerized film. It was never played after the premiere and wasn't recorded until more than 70 years later. Metropolis wasn't quite a blank canvas, but it was often a blank musical canvas. Artists began to wonder what this future city might sound like.

Likely the most influential electronic music band in history, Kraftwerk were never shy about the influence of Metropolis on their sound and aesthetic. "We were very much influenced by the futuristic silent films of Fritz Lang," Kraftwerk's Ralf Hütter said. "We feel that we are the sons of that type of science fiction cinema. We are the band of Metropolis. Back in the '20s, people were thinking technologically about the future in physics, film, radio, chemistry, mass transport…everything but music. We feel that our music is a continuation of this early futurism. When you go and see Star Wars, with all its science fiction gadgets, we feel embarrassed to listen to the music…19th century strings! That music for that film!? Historically, we feel that if there ever was a music group in Metropolis, maybe Kraftwerk would have been that band." [5]

Kraftwerk never made a soundtrack for Metropolis (though they were allegedly asked once to create one). [6] The band did however reference several of the film's concepts on their 1978 album Die Mensch-Maschine and more directly on the album's third track, "Metropolis."

Film restoration and music came together on Giorgio Moroder's 1984 edit of the film. The Italian producer worked with film historians and experts to release a new 83 minute version of Metropolis along with a soundtrack featuring ten songs written and produced by Moroder and performed by '80s rock radio stars from Freddie Mercury to Pat Benatar and Billy Squier. Founding member of both Kluster/Cluster and Harmonia Dieter Moebius also composed a notable soundtrack for Metropolis, released posthumously as Musik für Metropolis in 2017.

The various reconstruction efforts gave Metropolis a strange dynamism from 1980 onward, especially for a silent film. It was a work of art in a state of constant renewal — and with each alteration, the film improved. New restorations followed Moroder's with releases in 1987 and 2001. In 2010, The Complete Metropolis was released based upon a re-discovered safety print of Lang's original, with 25 minutes of footage not seen in 80 years.

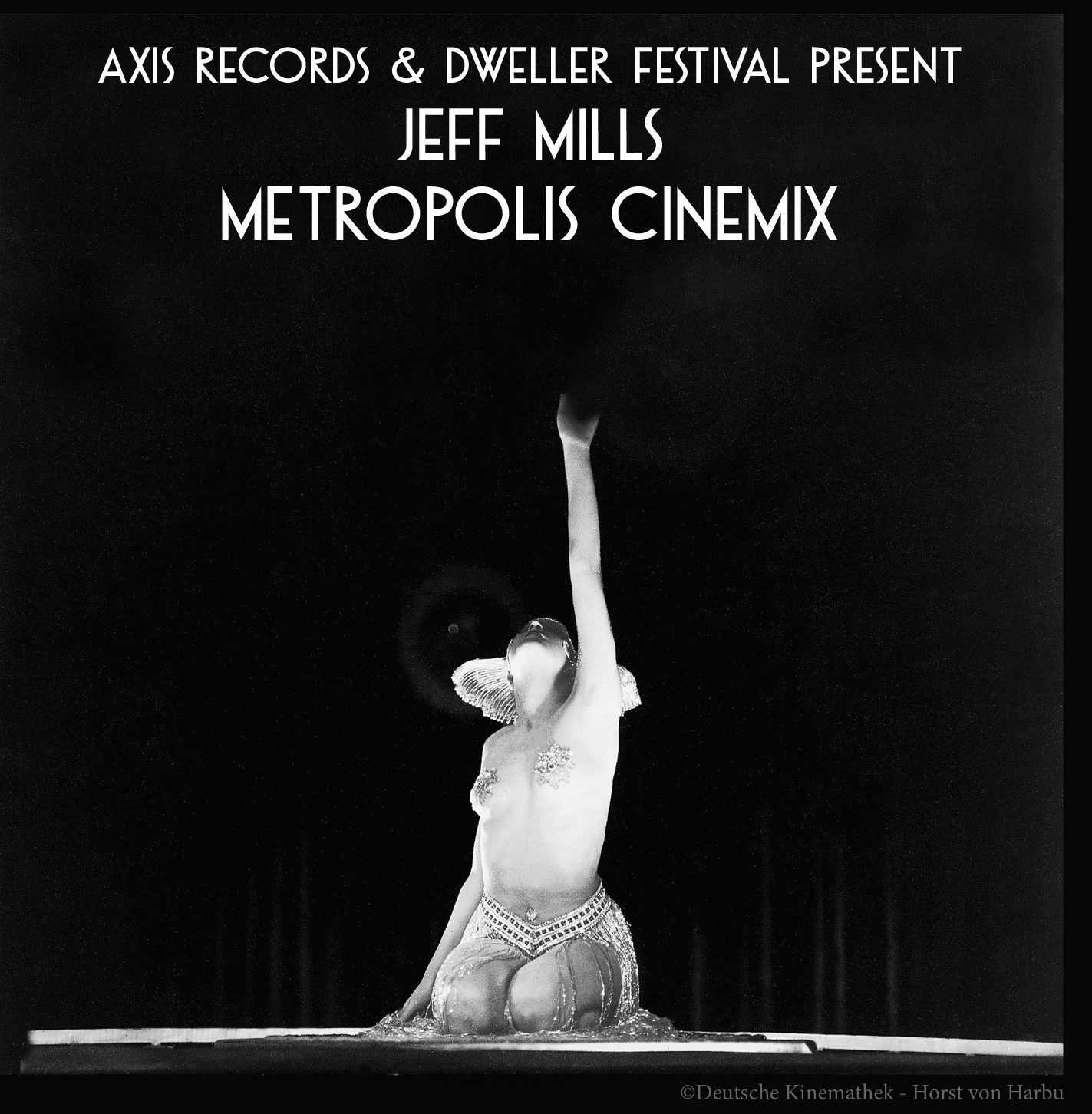

Jeff Mills released his first soundtrack for Metropolis in 2000. Praising the film's "timeless message of solidarity," Mills stated that his objective was to "reintroduce and educate the theories and ideology" of Metropolis to the youth at the end of one century and beginning of a new one.

Mills wrote a second soundtrack for Metropolis in 2010. This is the third. These are not drafts of a single work in progress, but entirely separate compositions, with original music, and each written from a different and unique perspective. The 2000 soundtrack was released from the perspective of a spectator watching the screen. The 2010 soundtrack was from the perspective of the characters in the film watching the spectators watching the screen. This 2022 soundtrack is from the perspective of Metropolis' machines and technology and composed as a "symphonic electronic soundtrack," played by an orchestra of machines with a conductor presiding.

After “the last two previous versions made back in 1999 and in 2010, I thought it was time to revisit the film since so much had changed in the world and with people (in general). This new soundtrack is more emotional and deeper."

Mills has performed the scores many times over the years, "from large auditoriums to churches to projections on garage doors. But with every showing, there is always the understanding that its important to show this film to the public. That it’s not just a movie — it’s more about lessons about the human spirit that every one of us should be reminded of.”

Let No One Stay Behind

Every generation likely believes that the world and the message of Metropolis is more relevant to us, and our times, than any that came before. I imagine this will always be the case. Like all great myths, the story of Metropolis will be repeatedly reinterpreted, re-fit to take into account new realities.

Similarly, the broadest themes of Metropolis would likely be as meaningful to people backward as well as forward — to an Egyptian laborer crafting the funeral monuments of his living god, the Haitian farmer driven by poverty to uproot himself for Cité Soleil, the housekeeper sleeping in her car after cleaning the homes and offices of the new Silicon Valley elite.

Metropolis holds up a gloomy mirror to America in 2022. For many in this country, the pandemic was their first encounter with an explicitly class-based system, this one divided between the "essential" and "non-essential." (the "essential" perversely were the worst-paid and ill-treated ones.) In the Spring of 2020, I frequently looked out a window at the modern towers erected during the 2010s real estate boom across America — glass and steel skyscrapers like Fritz Lang’s “vertical veil, shimmering, almost weightless, a luxurious cloth hung from the dark sky to dazzle, distract and hypnotize.” Every light was blazing, every “non-essential” soul safely at home. Down deserted streets pedaled delivery drivers, square foil-lined boxes strapped to their backs, ”essential workers" bringing food, toilet paper and alcohol to the doorsteps of the “non-essential.” These desolate shots of America under lockdown were among the most “Metropolian” visions I've ever seen — until a few months later, when waves of rioters crashed into the same towers, looting the high-end street-level stores but leaving the occupants of the towers above them untouched. The next day this tide of humanity receded out but the bridges over the Chicago River were raised, underground subways blocked to prevent them from coming back from the catacombs.

For these reasons, when I watched the 2010 restoration of Metropolis I found myself fascinated by the character of Josaphat, Fredersen's assistant. Fredersen fires Josaphat (Hebrew for “Yahweh has judged”) for not informing him of the “Moloch” factory explosion before Freder told him about it.

Josaphat nearly kills himself over this, but not out of shame. As Freder warns to his father, the only social mobility in Metropolis points downward. Losing his employment with the elite means Josaphat will now descend to the worker's city underground, a prospect viewed as a fate worse than death.

Antonio García Martínez characterized a part of American society in 2018 as slightly more advanced than that of Metropolis: he divided it into four castes rather than two, but each lower class sharing Josaphat's terror of slipping down the social ladder. Those below the elites can only dream of being able to "drive/shop/handyman enough to rise" upward to a higher class. Practically, it never happens. [7] With the explosive growth of those employed but homeless in cities across Europe and America, we might also wonder if our leaders lack even the miserable humanity of Joh Fredersen early in Metropolis, who at least gave his workers their own city to sleep in. Maybe Fredersen was just smarter.

Later, when the Maschinenmensch incites the workers of Metropolis to revolt, they leave behind their children and then dance in celebration while they’re drowning in the city beneath their feet. The January 6 Insurrection was a tawdry, live action role playing session of this pivotal scene in the movie (without the workers’ underlying justification) as Donald Trump stoked his followers to tear apart another “metropolis.” This pique of vengeance lead to an orgy of violence and, as the film predicted, the eventual self-destruction of rioters themselves, deluded or seduced by the tools of our own century’s sunburned Rotwang. Lang and von Harbou warned us that the hands without the heart are just as dangerous as the head without the heart — and just as vicious.

These scenes from the modern world point to more than just the vague resemblance between art and life. Lang and von Harbou’s message is as relevant here as it was in 1927: that all of these constructions — these machines — were made by men, and are still controlled by men, to dominate their fellow men. A vicious economic system is not the creation of gods or nature, but a tool created by people to exploit other people. It’s a machine you can’t see, but it’s a machine just like the factories and turbines that devour human flesh.

In the world of the 21st century, we still fear that the machines are taking over — that the robots are winning. But if the robots do take over, the lesson of Metropolis is that it’s just humans behind them, and the same tools used to oppress humankind can also be used to liberate them.

That fear is unlikely to pass, but neither are the lessons of Metropolis. One hundred years into the future — two hundred years from when Metropolis was made — our machines will be more ubiquitous than ever. Already small machines connect to larger machines to carry out menial tasks on our behalf, a trend that will only grow as each become exponentially more powerful and efficient.

Yet with ubiquity comes invisibility, and with invisibility comes a new kind of dread. Just as few people will ever see a Google server, the machines of the future will be increasingly hidden from view and so embedded into daily life that they’re hard to even recognize as descendants of Freder’s industrial Moloch of the 1920s. We fear what we can’t see — the “terror of the night,” the “pestilence that stalks in darkness” — more than what we can. And we will still fear that these tools will feed upon our lives and our minds, their algorithms unleashed to manipulate reality around us, and us with it. Perhaps we’ll finally see the machine escape the control of mankind, but more likely it will still be one from a collection of tools that can exploited by their creators — the rulers of a future Metropolis — to turn humans against one another; used to launch a neo-elite even further into the skies than in the skyscrapers of Manhattan or Metropolis, exploring the solar systems and keeping others underground, “where they belong.”

This is the real source of the film's power. Metropolis invites us to take a snapshot of our world, hold it up against its own nightmare dystopia and use a red pen to circle everything that is the same. It's tempting to believe from the results of this test that the world is moving irrevocably toward the insanity of Metropolis.

Tempting, but wrong. Lang himself provides an answer to this, the overriding message of Metropolis and a secret that can bring down the worst in society and technology, which is to say the worst in people: solidarity. Or put another way:

"Look! These are your brothers."

[1] McGilligan, Patrick. Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast (St. Martin's Griffin Press, 1997).

[2] Kracauer, Siegfried. From Caligari to Hitler (North Rivers, 1947).

[3] “The 100 Greatest Films of All Time.” (Sight and Sound, Updated June 28, 2021)

[4] Elsaesser, Thomas. Metropolis. (BFI Publishing, 2000).

[5] Barr, Tim. Kraftwerk: From Dusseldorf to the Future (With Love) (Ebury Press, 1999).

[6] Schütte, Uwe. Kraftwerk (Penguin Books, 2021).

[7] Garcia Martínez, Antonio. "How Silicon Valley Fuels an Informal Caste System." (Wired, July 9 2018).

メトロポリス

by: テリー・マシュー

機械たちの弁明: メトロポリスの未来世界に対する新たな視点

ニューヨーク港に停泊中の船のデッキに上がり、水平線に畏敬の念を抱くフリッツ・ラング。ビザの問題が気になっているのではない。「敵性外国人」として拘束されるのはこれが初めてではない。翌日には釈放され、ドイッチュラント号から下船することができるだろう。

しかし、ラングはここで、「ドイツ」という船に足をかけ、マンハッタンの街並みを見つめながら、それまで作られたことのないような次回作の構想を練ったのである。

「ネオンの光で真っ昼間のように照らされた通りが見えた」と、彼は後に語っている。その上には特大の広告があり、回転し、点滅し、螺旋を描いていた...当時のヨーロッパ人にとっては全く新しい、おとぎ話のようなものだった。

ビルは垂直のヴェールのようで、きらめき、ほとんど重さを感じさせず、暗い空から豪華な布を垂らして、まばゆく、気をそらし、催眠術をかけているようだ」。夜、街は生きているという印象を与えず、幻想が生きているように生きていた。[1]

ラングは後に、ピーター・ボグダノヴィッチ監督に、「そこで私は『メトロポリス』を構想した」と語っている。

この話は完全な真実ではない。ラングとドイツの大手スタジオUFAのプロデューサー、エーリッヒ・ポンマーが1924年にSS Deutschland号に乗り込む前に、当時の妻テア・フォン・ハーブーが脚本を書くなど、『メトロポリス』の準備が進んでいたことは十分に証明されている。しかし、記号論の達人であるラングは、良いシンボルは見ればすぐにわかる。この寓話は、彼の画期的な映画をドイツ的であると同時に国際的なものとして記念するものであり、『メトロポリス』製作の背後にある基礎的な神話となったのである。

いずれにせよ、ニューヨークの電気的な大聖堂が、『メトロポリス』の衝撃的な映像にインスピレーションを与えたことは疑いようがない。ラングは「ひどく暑かった」と回想している。「盲目で混乱した人間の力が押し合いへし合いしているクレーターのような人間の渦」であった、と。

ラングと『メトロポリス』が何に触発されたのか、視覚芸術や絵画の参照、そして映画の象徴であるアンドロイド、マシーネンメンシュの顔のインスピレーションとなった部族のマスクについては、複数の本が書かれている。しかし、なぜ『メトロポリス』は私たちにインスピレーションを与え続けるのだろうか。この無声映画、そのメッセージとテーマが、最も著名な音楽家たちの心を動かし、音楽にしたのはなぜなのか。そして、なぜ多くの電子音楽作曲家が、100年以上も前の未来についての映画に魅了されているのだろうか。

『メトロポリス』は、当時、複数の批評家から「おとぎ話」とこき下ろされた。公開当時は人気もなく、巨額の予算を回収することも困難であったろう。また、この映画のプロットには「共産主義的」なメッセージが含まれていると指摘し、地に落ちた労働者が支配階級に反旗を翻すとどうなるか、という警告を発していると批判する人もいた。ドイツの社会学者、作家、批評家であるジークフリート・クラッカウアーは、この作品は当時のドイツ社会の大空の下で固まりつつあった原始的なファシズムの理想を捉えていると主張した[2]。ドラマの批評家は、このストーリーを単純で「くだらない」、ほとんど恥ずかしいものだと見下した。

映画会社の重役たちはこの映画を大惨事とみなし、ドイツでの初公開後、映画の1/4以上をカットすることになる。ナチスはさらに削った。ラング監督は、「史上最も高価な映画」と言われたこともあり、どこで失敗したのか、誰もが見当がついていた。

しかし、『メトロポリス』が前世紀に渡り、散逸したプリントやナチスの検閲官のメモから再び組み立てられるにつれ、フリッツ・ラングのビジョンの範囲が明らかになった。「Sight and Sound」誌の影響力のある投票では、アルフレッド・ヒッチコックの『サイコ』と同率35位にランクインしている。[3] そして多くの点で、1927年に批評家たちが取り上げたこれらの「欠点」こそが、この映画に、他の方法では無声映画を見ることのなかった観客に突き抜ける力を与えているのである。『メトロポリス』において、ラングとフォン・ハーブーは、古い神話の殻の中に新しい神話を構築した。それは、子供たちが簡単に話して理解することができ、また、意味を求める学者や賢者が解釈、分析、熟考することができるものである。

ある日、地底の人達があなたに反抗してきたら?

『メトロポリス』の舞台は、同名の都市で、ある時点の未来である(2000年、2026年、3000年はすべて、長年にわたってこの映画に関係するさまざまな存在によって言及されてきた)。社会は激しく階層化され、街のエリートたちはアールデコの巨大な高層ビルの頂上で退廃的な生活を送っている。一方、労働者たちは、工場から地下街の自宅まで、ロボットのように足早に移動している。健康、新鮮な空気、そして幸せさえも、生まれながらのエリートの特権であるかのように見える。

メトロポリスの支配者の息子フレダーは、厳選された花嫁を手に入れようとしたとき、ひとりの女性マリアが地下から貧しい子供たちを連れて「永遠の庭園」を突破してきた。その沈んだ瞳は、彼女が華やかな人々に身振りで語りかけると、あたりを見回す。"見なさい、この人たちはあなたの兄弟よ "と子供たちに言う。

この言葉こそが、メトロポリスを破滅と救済へと導く、筋書きの火付け役となったのだ。動揺したフレダーはマリアの後を追ってよろめき、何人もの労働者が犠牲になる産業事故を目撃する。その直後、彼は巨大な工場が人間の生け贄の神モロクに変貌し、労働者を "機械の生きた餌 "としてむさぼり食う姿を幻視する。

フレダーは、父であるヨハン・フレダーセンに何が起こったかを伝えようと走り出す。フレダーセンは知らなかったし、フレダーは父親が経済的な悲劇ではなく、人間的な悲劇としてそれを気にかけるかもしれないと信じるほどナイーブなのだ。

このシーンは、『メトロポリス』の中で最も重要な台詞の一部である。1927年の観客は、この種の悪徳実業家を確かに知っていたし、工場や鉱山での雇用がもたらす死や醜聞の危険も知っていたのである。

"ある日、深みにいる者たちがあなたに対して立ち上がることがあったらどうしますか?" フレダーは父に尋ねる。フレダーは、このような状況が意図的に存在することーなぜなら労働者を使い捨ての道具として、機械よりも価値のないものとして扱った方が、より利益が大きいからだ ーを想像できない、限りなく楽観的な若者だ。フレダーセンはただ微笑むだけだ。

「お父さん、あなたの街を作った人たちはどこにいるのですか?」フレダーは、数十年、いや数百年にわたる社会的対立を見据えた問いかけをする。この言葉は、2022年、アフリカ人奴隷の子孫による制度的人種差別との闘いに関連して、再び語られることが想像される。私たちの都市を建設するために体を壊した人々は、いったいどこにいるのだろうか。

メトロポリスの支配者のような残忍な率直さを持ち合わせていないため、現在の指導者たちは誰も私たちに答えてくれない。彼はこう答える。"彼らが属する場所 "だ、と。

機械に死を

父と別れたフレダーは、死者の一人が持っていた地図を頼りにマリアを追い、労働者都市の地下にあるカタコンベに導かれる。そこでマリアは、原始的な十字架の説教壇の上で、疲れ果てた労働者たちに、来るべき救世主について語る--都市の手(労働者)と頭(支配階級)を結びつける「調停者」だ。彼女はバベルの塔のたとえを、階級闘争の物語として語り出す。奴隷となった人々は、「人類」に捧げる神として昇る記念碑を建てるために、自分達を犠牲にした。

労働者たちは頭を下げる。『メトロポリス』が作られる何十年も前にアプトン・シンクレアが『ジャングル』で書いた、「男と女の労働力を搾取するシステムによる人間の心の破壊」と同じ貧しい労働者たちである。

しかし、労働者たちがマリアと一緒に宗教を実践する一方で、メトロポリスの支配者たちは独自の信条を持っている。フレダーセンは、マッドサイエンティストの原型であり、専門家が失敗したときに訪れる魔術師のような存在でもあるロットワングと一緒にこの会合を監視している。ロットワングはまた、メトロポリスの2つのカーストをつなぐ存在であるが、それを両者の仲介に使うのではなく、復讐の計画を進めるために使うのである。ロットワングは、フレダーセンのために彼を捨て、死ぬ前にフレダーを産んだ彼の失恋相手、ヘルの顔を記念する巨大な彫刻を作った。彼は彼女を模したアンドロイド、Maschinenmensch(機械人間)を造った。その製造過程で手を失い、黒い手袋をはめた機械仕掛けの義手と取り替えた。フレダーゼンはマシーネンメンシュを使って労働者を破壊し、挑発しようと考えている。ロットワングはそれを使って都市を、ひいてはフレダーセンを破壊しようと計画している。彼はこの映画の中で唯一機械の一部である人間のキャラクターであり、機械を破壊するために別の機械を作った。

『メトロポリス』は、表面的には、人間対機械についての映画である。しかし、ラングとフォン・ハーボウが『メトロポリス』の機械を「悪」として描いているわけではないことに注目することが重要だ。その後に製作されたディストピア映画の大部分(そしてその影響を直接受けた映画の多く)とは異なり、『メトロポリス』の機械は単なる道具にすぎないのである。この映画には、監視技術も、拷問装置も、冷徹な計算で人々を殺害する悪性のコンピューターも出てこない。しかし、人間はそうしたことを行っている。フレダーのビジョンに反して、メトロポリスの機械はモロクではない。人間が他の人々を死の淵に追いやっているのだ。フレダーは潜入捜査中、10時間勤務という過酷なスケジュールをこなす。このスケジュールは父親が意図的に決めたもので、父親はオフィスの壁に特別な10時間時計を飾っているが、自分の腕時計は通常の方法で時間を知らせている。

同様に、マシーネンメンシュはテロリストであるが、それはテロリストの手中にあるからであり、言われたことをやっているだけである。労働者に反乱を呼びかけるのは、メトロポリスの支配階級を攻撃するためではなく、"機械に死を!"と要求するためなのだ。ロットワングからの指示で、フレダーセンのような支配階級の一員を攻撃しても、他の誰か、より悪いかもしれないが、確実に良い人がメトロポリスをリードすることになるだけだと理解しているようである。しかし、マシンを攻撃すれば、全員が破滅することになる。

マシーネンメンシュに憤慨した労働者たちは、子供たちを捨ててメトロポリスを破壊する。しかしその後、彼らは自分たちが "殺した "機械のひとつであるハートマシンが、自分たちの地下の家を支えていることに気づく。洪水が都市を破壊する中、マリアはもう一つの機械、都市の広場にある巨大な鐘を積極的に利用し、捨てられた子供たちを安全な場所へと導いていく。

『メトロポリス』は、テクノロジーが人間の支配から逃れる物語ではない。この映画は、テクノロジーが人間の支配下にしっかりと置かれた話であり、あらゆる道徳から切り離された冷酷な人間たちの話なのだ。これこそが、この映画のエピグラムの背後にある意味であり、頭と手の間を取り持つのは心でなければならないという、この映画のメッセージが持続している理由の一つである。ロボットや機械の打倒が目的ではない。それを操る人間、連帯感、そしてそれを取り戻す方法がテーマなのだ。

世界が悪魔になるのを見届けよう

『メトロポリス』は、公開時に乱造された唯一の古典映画ではないが、古典映画を再び縫い合わせることに最も成功した例かもしれない。UFAのアメリカの配給会社パルファメット(パラマウントとMGMの共同企業体)は、大幅なカットを命じた。アメリカの作家チャニング・ポロックが雇われ、既存の映像から「新しい」物語を組み立てる編集を行った。ポロックは、今日、ドロシー・パーカーの辛辣な批評(彼の劇『美しき家』は「最低の劇だ」と書いている)でのみ知られているが、アメリカ公開のために『メトロポリス』から少なくとも37分を削除している。ドイツでは、UFAを買収した実業家でありメディア王であるアルフレッド・ヒューゲンベルグが、この映画の政治的背景に着目し、オリジナルプリントのカットを行った。後にアドルフ・ヒトラーの第一次内閣の一員となるヒューゲンベルグは、スタジオにいた「共和主義者、ユダヤ人、国際主義者」をUFAから粛清することを目指したのである。ナチスが政権を握った後、『メトロポリス』はさらにカットされ、91分に短縮された。このカットは、1980年代以前に最もよく見られたバージョンである(ただし、検閲官の保存されたノートは、最終的に再構成するのに役立った)。

どう考えても、このカットは当時の映画の評価を高めることはなかった。前述したように、批評はかなり暗澹たるものだった。しかし、ラングとフォン・ハーボウを酷評した批評家の多くは、この映画のまばゆいばかりの視覚的光景に不本意ながら敬意を払っていたのである。評論家のトマ・エルセッサーによれば、フランスの『レ・アナル』の批評家は、この映画の "思わせぶり"、"気取り"、"比類なき愚かさ "を攻撃しながら、ラングには "並外れた映像と想像力がある "と評価している。同様に、映画監督のルイス・ブニュエルは、この映画のつまらない、気取った(またしても)、衒いのある "陳腐なロマン主義 "をバッシングしている。彼はまた、この映画が「想像しうる最も素晴らしい絵本のように私たちを圧倒することができる」とも考えていた。[4]

しかし、ラングは単にセットをネオンやクロームで着飾ったのではない。この映画が長く愛される秘密のひとつは、不思議なことに、画面に「未来の技術」がほとんど登場しないことにある。マシーネンメンシュを除けば、メトロポリスのテクノロジーはほとんどすべて1920年代のものである。フレダーセンとロットワングは、小さな手の懐中電灯に導かれてカタコンベを歩いている。フレダーセンの不吉な子分である「薄い男」は、車の後部座席のパネルから電話を取り出している。1920年代にはクレイジーなことだったのだろうが、時が幸いして現実のものとなったのだ。メトロポリスでは、未来への盲目的な一歩を踏み出すことは、他にほとんどない。車はT型。複葉機は、街の鉄骨の回廊をブンブン飛んでいる。重機は重機のように見える。誰もアルミホイルの帽子をかぶったり、蛍光色の服を着たり、レーザー銃を撃ったりはしていない。

批評家たちは、『メトロポリス』が明確な予測をすることなく「未来について語るふりをしている」と主張した、とエルセッサーは書いている。しかし、実現しない「想像上の未来」ほど、早く老朽化するものはない。現代の観客は、来なかった未来のキッチュな宇宙服や流線型のジェットカーよりも、複葉機や1920年代のファッションを受け入れ、それ以外を想像している可能性が高いのだ。この映画が100年後に現代的である理由のひとつは、メトロポリスに触れることができるように感じられるからである。都市とそのセットは、厚紙がへこんだり、引っ掻いてもホイルがはがれたりすることなく、堅固に感じられるのだ。

今、多くの人が死者の街へ

切り詰められた形であっても、『メトロポリス』は何世代にもわたって映画制作者やアーティスト、特に音楽家にインスピレーションを与え続けた。多くの人が無言で、あるいは無関係の伴奏でこの映画を観た。オリジナルの楽譜が書かれたが、無味乾燥な映画には合わないということで、ほとんどの人が聞くことはなかった。初演後、演奏されることはなく、録音されたのは70年以上後のことである。メトロポリスは白紙のキャンバスではなかったが、しばしば音楽の白紙キャンバスであった。アーティストたちは、この未来都市がどのような音を奏でるのだろうかと考え始めた。

おそらく史上最も影響力のある電子音楽バンドであるクラフトワークは、メトロポリスが彼らのサウンドと美学に与えた影響について決して恥ずかしがることはなかった。「私たちは、フリッツ・ラングの未来的な無声映画にとても影響を受けました」とクラフトワークのラルフ・ヒュッターは言う。「自分たちはそのようなSF映画の息子だと感じている。私たちは『メトロポリス』のバンドなのだ。20年代、人々は物理学、映画、ラジオ、化学、大量輸送...音楽以外のすべてにおいて、未来について技術的に考えていた。私たちの音楽は、この初期のフューチャリズムの延長線上にあると感じています。『スター・ウォーズ』を観に行くと、SF的なガジェットの中に、19世紀の弦楽器!?あの映画の音楽が!?音楽を聴くのが恥ずかしい。歴史的に見れば、もしメトロポリスに音楽グループが存在するとしたら、クラフトワークがそのバンドだったのかもしれないと感じています」。[5]

クラフトワークは、『メトロポリス』のサウンドトラックを制作することはなかった(一度は制作を依頼されたと言われているが)。しかし、バンドは1978年のアルバム『Die Mensch-Maschine』で映画のコンセプトのいくつかに言及し、アルバムの3曲目 "Metropolis "ではより直接的な言及をしている[6]。

映画の修復と音楽は、1984年にジョルジオ・モロダーが手がけた映画の編集で一緒に行われた。このイタリア人プロデューサーは、映画史家や専門家と協力して、83分の新しいバージョンの『メトロポリス』をリリースし、モロダーが作曲・制作した10曲のサウンドトラックを、フレディ・マーキュリーからパット・ベナターやビリー・スクワイアまで80年代のロックラジオのスターが演奏している。クラスター/クラスターとハルモニアの両方の創設メンバーであるディーター・メビウスも、『メトロポリス』の注目すべきサウンドトラックを作曲し、2017年にMusik für Metropolisとして死後リリースされた。

さまざまな再構成作業によって、『メトロポリス』は1980年以降、特に無声映画としては不思議なダイナミズムを持つようになった。それは絶え間なく更新される芸術作品であり、改変されるたびに映画は向上していった。1987年と2001年には、モロダーの手による新たな修復版がリリースされた。2010年には、ラングのオリジナルの安全プリントを再発見し、80年ぶりに25分の映像を加えた『完全版メトロポリス』が公開された。

ジェフ・ミルズは2000年に『メトロポリス』のサウンドトラックを初めてリリースした。この映画の「時代を超えた連帯のメッセージ」を賞賛し、ミルズは、世紀の終わりと新しい世紀の始まりに、メトロポリスの「理論とイデオロギーを再導入し、教育する」ことが目的であると述べている。

ミルズは2010年に『メトロポリス』の2作目のサウンドトラックを作曲した。今回が3作目である。これらは、一つの作品の下書きではなく、全く別の作曲で、オリジナルの音楽を使い、それぞれ異なるユニークな視点から書かれたものである。2000年のサウンドトラックは、スクリーンを見ている観客の視点から発表された。2010年のサウンドトラックは、スクリーンを見ている観客を映画の中の登場人物が見ているという視点だった。今回の2022年版サウンドトラックは、メトロポリスの機械やテクノロジーの視点から、指揮者を主宰とする機械のオーケストラが奏でる「シンフォニックな電子サウンドトラック」として構成されている。

1999年と2010年に制作された前2作を経て、「世の中も人間も(一般的に)大きく変化しているので、そろそろ見直す時期だと思った。この新しいサウンドトラックは、よりエモーショナルで深みのあるものになっている」と言っている。

ミルズは、「大講堂から教会、ガレージのドアへの投影まで、長年にわたって何度もこのスコアを上演してきた。しかし、上映するたびに、この映画を一般に見せることが重要であることを常に理解している。これは単なる映画ではなく、私たち一人ひとりが思い出すべき人間の精神についての教訓なのだ」と。

誰も取り残されないように

どの世代も、『メトロポリス』の世界とメッセージは、それ以前のどの時代よりも、私たちや私たちの時代にふさわしいと信じていることだろう。私は、これは常にそうであると想像している。すべての偉大な神話のように、『メトロポリス』の物語は繰り返し再解釈され、新しい現実を考慮に入れるために再適合されるだろう。

同様に、『メトロポリス』の最も大きなテーマは、過去だけでなく未来の人々にとっても意味があるだろう。エジプトの労働者が生ける神の葬儀のモニュメントを作り、ハイチの農民が貧困に追い込まれてシテ・ソレイユに身を投じ、家政婦がシリコンバレーの新しいエリートたちの家やオフィスを掃除して自分の車で眠っているように、である。

『メトロポリス』は、2022年のアメリカを映す暗い鏡のような作品である。この国の多くの人にとって、パンデミックは、"必要不可欠 "と "不必要 "に分けられる、明らかに階級的なシステムとの最初の出会いであった。(2020年の春、私は頻繁に窓から2010年代の不動産ブームで建てられたアメリカ中の近代的なタワーを眺めていた。フリッツ・ラングの「垂直のベール、きらめき、ほとんど無重力、暗い空から豪華な布を垂らして眩惑し、気をそらし、催眠術にかける」ようなガラスと鉄の超高層ビルだ。すべての明かりが輝き、「必要でない」人たちはみな安全に家にいる。閑散とした通りを、ホイルで覆われた四角い箱を背負った配達人がペダルを踏み、「必要不可欠な労働者」が「必要不可欠ではない」人々の玄関先に食料、トイレットペーパー、アルコールなどを運んでいく。数ヵ月後、暴徒の波が同じタワーに押し寄せ、高級路面店は略奪されたが、その上のタワーの住人は無傷だったのだ。翌日、この人の波は引いたが、シカゴ川にかかる橋は持ち上げられ、地下の地下鉄は封鎖され、地下墓地から戻ってくるのを防いだ。

こうした理由から、2010年に修復された『メトロポリス』を観たとき、私はフレダーセンの助手であるヨサファットの人物像に惹かれたのであった。フレダーセンは、「モロク」工場の爆発をフレダーから知らされる前に知らせなかったヨサファット(ヘブライ語で「ヤハウェが裁いた」という意味)をクビにする。

ヨサファットはこのことで自殺しそうになるが、恥からではない。フレダーが父に警告したように、メトロポリスでは社会的な移動は下向きにしかないのだ。エリートとの雇用を失うことは、ヨサファットが地下の労働者の街に降りていくことを意味し、それは死よりも悪い運命とみなされる。

アントニオ・ガルシア・マルティネスは、2018年のアメリカ社会の一部を、『メトロポリス』の社会よりわずかに進んだものとして特徴づけた。彼は、社会を2つではなく4つのカーストに分けたが、それぞれの下層階級は、ヨサファトが社会階層から滑り落ちる恐怖を共有していた。エリート以下の人々は、より高い階級に「上がるのに十分な運転/買い物/手仕事」ができることを夢見るしかない。現実的には、それは決して実現しない。[7] ヨーロッパやアメリカの都市では、雇用されていながらホームレスになる人々が爆発的に増えており、われわれのリーダーは、少なくとも労働者に自分の街で眠ることを与えた『メトロポリス』の初期のヨハン・フレダーセンのような惨めな人間性さえ欠いているのではないかとも考えてしまうだろう。フレダーセンの方が賢かっただけかもしれない。

その後、マシーネンメンシュがメトロポリスの労働者たちを反乱に駆り立てると、彼らは子供を置き去りにし、足元の街で溺れながら祝いのダンスを踊るのである。1月6日の反乱は、映画のこの重要なシーン(労働者の正当な理由がない)を、ドナルド・トランプが別の「メトロポリス」を引き裂こうと信奉者を煽る、下品な実写のロールプレイの場であった。この復讐心に駆られて、暴力の乱痴気騒ぎが起こり、映画が予測したように、暴徒たち自身が、私たちの世紀の日焼けしたロットワングの道具に惑わされ、あるいは誘惑されて、最終的に自滅するのである。ラングとフォン・ハーブーは、心なき手は心なき頭と同じように危険であり、同じように凶悪であると警告している。

これらの現代世界の光景は、芸術と生活のあいまいな類似性以上のものを指し示している。ラングとフォン・ハーボウのメッセージは、1927年当時と同様に、ここでも重要である。これらの構築物、つまり機械はすべて、人間が仲間を支配するために作ったものであり、今も人間によって支配されているのだ。悪質な経済システムは、神や自然が作り出したものではなく、人間が他の人間を搾取するために作り出した道具である。目に見えないが、人間の肉をむさぼる工場やタービンと同じような機械なのだ。

21世紀の世界では、いまだに機械に支配されること、つまりロボットが勝利することを恐れている。しかし、もしロボットが支配したなら、『メトロポリス』の教訓は、その背後にいるのは人間であり、人類を抑圧するために使われるのと同じ道具が、人類を解放するためにも使われうるということである。

その恐怖は過ぎ去ることはないだろうが、『メトロポリス』の教訓もまた然りである。100年後の未来、つまり『メトロポリス』が作られた200年後の未来では、私たちの機械はこれまで以上に普遍的になっているだろう。すでに小さな機械は大きな機械に接続され、私たちに代わって雑務をこなしている。この傾向は、それぞれの機械が指数関数的に強力かつ効率的になるにつれて、さらに強まっていくだろう。

しかし、普遍性には不可視性が伴い、不可視性には新しい種類の恐怖が伴う。グーグルのサーバーを目にする人がほとんどいないように、未来の機械はますます視界から隠され、日常生活に深く入り込み、1920年代のフレダーの産業モロクの子孫であることさえ認識しづらくなっていくことだろう。私たちは、見えるものよりも見えないもの、つまり「夜の恐怖」「暗闇を闊歩する疫病」を恐れる。そして、これらの道具が私たちの生活や心を蝕み、そのアルゴリズムが私たちの周りの現実を操作するために解き放たれ、私たちも一緒に操作されることを、私たちはまだ恐れるだろう。おそらく最終的には、マシンが人類の支配から逃れるのを見ることになるだろう。しかし、よりありそうなのは、未来のメトロポリスの支配者であるクリエイターが、人間を互いに対立させるために悪用できるツールのコレクションの一つであることだ。マンハッタンやメトロポリスの高層ビルよりもさらに上空に新エリートを送り込み、太陽系の探索と他の人々を「あるべき」地下に留めるために使われる。

これこそ、この映画の力の本当の源である。『メトロポリス』は、私たちの世界のスナップショットを撮り、悪夢のようなディストピアと重ね合わせて、赤ペンで同じところをすべて丸で囲むように誘いかける。このテストの結果から、世界は『メトロポリス』の狂気に向かって取り返しのつかない方向に進んでいると信じたくなる。

誘惑的だが、しかしそれは間違っている。ラング自身がその答えを提示している。『メトロポリス』の最大のメッセージであり、社会や技術の最悪の部分、つまり人間の最悪の部分を崩壊させることができる秘密、それが「連帯」である。別の言い方をすれば

"見なさい!彼らはあなたたちの兄弟なのです"。

[1] McGilligan, Patrick. Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast (St. Martin's Griffin Press, 1997).

[2] Kracauer, Siegfried. From Caligari to Hitler (North Rivers, 1947).

[3] “The 100 Greatest Films of All Time.” (Sight and Sound, Updated June 28, 2021)

[4] Elsaesser, Thomas. Metropolis. (BFI Publishing, 2000).

[5] Barr, Tim. Kraftwerk: From Dusseldorf to the Future (With Love) (Ebury Press, 1999).

[6] Schütte, Uwe. Kraftwerk (Penguin Books, 2021).

[7] Garcia Martínez, Antonio. "How Silicon Valley Fuels an Informal Caste System." (Wired, July 9 2018).

Metropolis

by: Terry Matthew

A la défense des machines : Un nouveau regard sur le monde futuriste de Metropolis

Retenu toute la nuit pendant que les autorités exminent ses papiers, Fritz Lang monte sur le pont d'un navire amarré dans le port de New York et contemple l'horizon avec admiraHon. Ses problèmes de visa ne sont pas alarmants ; ce n'est même pas la première fois que le réalisateur est détenu en tant qu’"étranger ennemi". Il sera libéré et autorisé à débarquer du SS Deutschland lorsque les choses seront réglées le lendemain.

Mais c'est là - les pieds sur un navire appelé "Allemagne" et le regard fixé sur la ligne d'horizon de ManhaVan - que Lang a eu une vision pour son prochain film, un genre de film qui n'avait jamais été fait auparavant.

"J'ai vu une rue éclairée comme en plein jour par des néons", dira-t-il plus tard. "Au-dessus d'elle, il y avait des publicités lumineuses surdimensionnées, qui tournaient et clignotaient en spirale... quelque chose de complètement nouveau et de presque féerique pour un Européen à ceVe époque...

"Les bâHments semblent être un voile verHcal, chatoyant, presque sans poids, un Hssu luxueux suspendu au ciel sombre pour éblouir, distraire et hypnoHser. La nuit, la ville ne donnait pas l'impression d'être vivante : elle vivait comme vivent les illusions." [1]

"C'est là", dira plus tard Lang au réalisateur Peter Bogdanovich, "que j'ai conçu Metropolis".

CeVe histoire n'est pas enHèrement vraie. De nombreux éléments prouvent que les préparaHfs de Metropolis étaient en cours - le scénario ayant été écrit par sa femme de l'époque, Thea von Harbou - avant que Lang et le producteur Erich Pommer du géant allemand des studios UFA n'embarquent sur le SS Deutschland en 1924. Mais Lang, maître de la sémioHque, savait reconnaître un bon symbole quand il en voyait un. CeVe fable, qui a permis à son film révoluHonnaire d'être à la fois allemand et internaHonal, est devenue le mythe fondateur de la réalisaHon de Metropolis.

Pourtant, il ne fait aucun doute que les cathédrales électriques de New York ont réellement inspiré les images choquantes de Metropolis, tout comme les Américains qu'il a rencontrés lorsque les deux Allemands se sont promenés dans la ville le lendemain. Il faisait "terriblement chaud", se souvient Lang, un maelström d'humanité comme un "cratère de forces humaines aveugles et confuses - se bousculant et se broyant les unes les autres".

De mulHples livres ont été écrits sur ce qui a inspiré Lang et Metropolis, les références aux arts visuels, aux peintures et aux masques tribaux qui ont inspiré le visage du Maschinenmensch, l'androïde emblémaHque du film. Mais pourquoi Metropolis conHnue-t-il de nous inspirer ?

Qu'est-ce qui, dans ce film muet, dans son message et ses thèmes, a poussé certains de nos plus célèbres musiciens à le meVre en musique ? Et pourquoi tant de compositeurs de musique électronique en parHculier, sont-ils fascinés par un film sur le futur qui a plus de 100 ans ?

Metropolis a été qualifié de "conte de fées" par plus d'un criHque à son époque. Le film n'a pas été un succès populaire lors de sa sorHe, et il aurait de toute façon été difficile pour le film de rentabiliser son gigantesque budget. Certains ont criHqué ce qu'ils considéraient comme un message "communiste" dans l'intrigue, un averHssement sur ce qui pourrait arriver lorsque des travailleurs poussés à bout se soulèvent contre la classe dirigeante. Le sociologue, écrivain et criHque allemand Siegfried Kracauer a soutenu qu'il capturait les idéaux proto-fascistes qui s'accumulaient sous le firmament de la société allemande de l'époque[2]. Les criHques dramaHques ont rejeté l'histoire comme étant simple, "puérile", presque embarrassante.

Les responsables du cinéma y voyaient une catastrophe et ont coupé plus d'un quart du film après sa première en Allemagne. Les nazis en ont coupé encore plus. Jugé comme le film le plus cher jamais réalisé, tout le monde avait une idée de ce qui n'allait pas chez Lang.

Mais au fur et à mesure que Metropolis a été reconsHtué au cours du siècle dernier - à parHr de copies éparses et des notes d'un censeur nazi - l'ampleur de la vision de Fritz Lang est devenue claire. Metropolis a fait l'objet d'une réévaluaHon criHque et est aujourd'hui considéré comme l'un des plus grands films jamais réalisés - le sondage influent de Sight and Sound l'a classé en 35e posiHon, à égalité avec ‘Psychose’ d'Alfred Hitchcock. [3] Et à bien des égards, ce sont ces "défauts" relevés par les criHques en 1927 qui donnent au film son pouvoir de percer auprès de publics qui, autrement, n'auraient jamais regardé un film muet. Dans Metropolis, Lang et von Harbou construisent une nouvelle mythologie dans la coquille de l'ancienne - une mythologie qui peut être racontée simplement et comprise par les enfants, mais aussi interprétée, analysée et ruminée par les savants et les sages en quête de sens.

Et si un jour ceux des profondeurs se soulèvent contre vous ?

Metropolis se déroule dans une ville au nom éponyme, à un moment donné dans le futur (les années 2000, 2026 et 3000 ont toutes été menHonnées par diverses enHtés liées au film au fil des ans). La société est devenue intensément straHfiée, les élites de la ville menant une vie décadente au sommet de gigantesques graVe-ciel art déco. Les ouvriers, quant à eux, se déplacent de manière roboHque de l'usine à leur maison dans une ville souterraine. La santé, l'air pur et, apparemment, le bonheur sont le privilège d'une élite bien née.

Freder, le fils du dirigeant de Metropolis, est sur le point d'avoir des rapports avec une courHsane triée sur le volet lorsqu'une femme, Maria, pénètre dans le jardin éternel avec une

poignée d'enfants mendiants venus du sous-sol. Leurs yeux enfoncés regardent autour d'eux tandis qu'elle fait des gestes vers les personnes glamour. "Regardez", dit-elle aux enfants, "ce sont vos frères".

Ce sont les mots qui enflamment l'intrigue et propulsent Metropolis vers la destrucHon et la rédempHon. Freder, ébranlé, suit Maria en Htubant et assiste à un accident industriel qui tue plusieurs ouvriers. Après l'accident, il a des hallucinaHons de l'usine gigantesque transformée en Moloch, dieu du sacrifice humain, dévorant les ouvriers comme "nourriture vivante pour les machines".

Freder court raconter à son père, Joh Fredersen, ce qui s'est passé. Fredersen ne savait pas, et Freder est assez naïf pour croire que son père pourrait s'intéresser à ceVe tragédie humaine plutôt que financière.

CeVe scène conHent certains des dialogues les plus importants de Metropolis. Le public de 1927 connaissait certainement ce type d'industriel malfaisant, ainsi que les dangers de mort ou de défiguraHon liés à l'emploi dans les usines et les mines.

"Et si un jour ceux des profondeurs se soulèvent contre toi ?" demande Freder à son père. Freder est ce jeune opHmiste sans limite qui ne peut imaginer que ces condiHons existent à dessein, parce qu'il est plus rentable de traiter les travailleurs comme des ouHls jetables, moins précieux que les machines qu'ils servent. Fredersen se contente de sourire.

"Où sont les gens, père, dont les mains ont construit ta ville ?" demande Freder, dans une quesHon qui plane sur des décennies et bientôt des siècles de conflit social. On peut presque imaginer que ces mots soient prononcés à nouveau, en 2022, dans le cadre de la luVe contre le racisme systémique menée par les descendants d'esclaves africains. Où sont en effet les personnes dont les corps ont été brisés pour construire nos villes ?

Aucun de nos dirigeants ne nous répond, car ils ne possèdent pas la franchise brutale du dirigeant de Metropolis. Il répond : "Là où est leur place."

Mort aux machines

QuiVant son père, Freder poursuit Maria à l'aide d'une carte trouvée sur l'un des morts, le conduisant sous terre dans des catacombes sous la cité ouvrière. Là, sur une chaire de croix primiHves, Maria parle aux ouvriers épuisés d'un messie à venir - un "médiateur" qui réunira les mains (les ouvriers) et la tête (la classe dirigeante) de la ville. Elle raconte à nouveau la parabole de la tour de Babel comme une histoire de luVe des classes - des gens asservis pour construire un monument à l'humanité s'élevant comme un dieu, dédié à "l'humanité", tout en étant privés de la leur.

Les ouvriers baissent la tête. Ce sont les mêmes travailleurs pauvres dont parlait Upton Sinclair dans La Jungle, des décennies avant la réalisaHon de Metropolis, qui décrivait "la rupture des cœurs humains par un système qui exploite le travail des hommes et des femmes".

Mais tandis que les ouvriers praHquent leur religion avec Maria, les dirigeants de Metropolis ont leur propre credo. Fredersen espionne ceVe réunion aux côtés de Rotwang, archétype du savant fou mais aussi une sorte de magicien auquel Fredersen rend visite lorsque ses experts lui font défaut. Rotwang est également un lien entre les deux castes de Metropolis, mais il l'uHlise non pas pour servir de médiateur entre elles, mais pour faire avancer ses plans de vengeance.

Rotwang a construit une sculpture massive commémorant le visage de Hel, son amour perdu qui l'a quiVé pour Fredersen et a donné naissance à Freder avant de mourir. Il a construit un androïde à son image - le Maschinenmensch ou l’Homme- Machine. Pendant sa construcHon, il a perdu une main et l'a remplacée par une prothèse mécanique recouverte d'un gant noir.

Fredersen voudrait uHliser le Maschinenmensch pour subverHr et provoquer les ouvriers afin de les détruire. Rotwang prévoit de l'uHliser pour détruire la ville et donc Fredersen. C'est le seul personnage humain du film qui fait parHe d'une machine, et il a construit une autre machine afin de détruire les machines.

Metropolis est - superficiellement - un film sur les hommes contre les machines. Mais il est important de noter que Lang et von Harbou ne présentent à aucun moment les machines de Metropolis comme "mauvaises". Contrairement à la grande majorité des films dystopiques produits dans son sillage (et à beaucoup de ceux directement influencés par lui), les machines de Metropolis ne sont que des ouHls. Il n'y a pas de technologie de surveillance dans le film, pas d'appareils de torture, pas d'ordinateurs malins qui assassinent les gens avec une logique froide et calculatrice. En revanche, ce sont des personnes qui font ces choses. Contrairement à la vision de Freder, les machines de Metropolis ne sont pas Moloch. Ce sont des personnes qui poussent d'autres personnes dans la gueule du loup. Pendant sa mission d'infiltraHon, Freder travaille 10 heures par jour - un horaire délibérément fixé par son père, qui a une horloge spéciale 10 heures qui domine le mur de son bureau, alors que sa propre montre-bracelet donne l'heure normalement.

De même, le Maschinenmensch est un terroriste mais seulement parce qu'il est entre les mains de terroristes ; il ne fait que ce qu'on lui dit de faire. Il appelle les ouvriers à se révolter non pas en s'aVaquant à la classe dirigeante de Metropolis mais en exigeant "Mort aux machines !".

D'après les instrucHons de Rotwang, il semble avoir compris que s'aVaquer à un membre de la classe dirigeante comme Fredersen conduirait simplement à ce que quelqu'un d'autre, peut- être pire mais certainement pas meilleur, dirige Metropolis. AVaquer les machines, cependant, assurerait la destrucHon de tout le monde.

Agacés par le Maschinenmensch, les ouvriers abandonnent leurs enfants pour semer la pagaille dans Metropolis. Ce n'est que plus tard qu'ils réalisent que l'une des machines qu'ils ont "tuées"

- la Heart Machine - alimente leurs maisons souterraines. Alors que les eaux de crue déchirent

leur ville, Maria uHlise une autre machine - une cloche géante sur la place de la ville - dans un but posiHf, en ralliant les enfants abandonnés pour les conduire en lieu sûr.

Metropolis n'est pas une histoire de technologie échappant au contrôle des hommes. C'est l'histoire d'une technologie très fermement sous le contrôle des hommes - des hommes sans cœur coupés de toute moralité. C'est le sens de l'épigramme du film - le médiateur entre la tête et les mains doit être le cœur - et l'une des raisons pour lesquelles le message du film a perduré. Il n'a jamais été quesHon de renverser les robots ou les machines. Il s'agit des personnes qui les contrôlent, de notre sens de la solidarité et de la façon dont nous pouvons le retrouver.

Regardons comment le monde court à sa perte

Metropolis n'est pas le seul film classique à avoir été massacré lors de sa sorHe, mais c'est peut- être le cas le plus réussi de recollage d'un film classique. Les distributeurs américains de UFA, Parufamet (une entreprise commune entre Paramount et MGM), ont ordonné des coupes importantes. L'auteur américain Channing Pollock a été engagé pour monter le film en une "nouvelle" histoire assemblée à parHr des séquences existantes. Pollock, connu aujourd'hui uniquement pour une criHque lapidaire de Dorothy Parker (sa pièce The House BeauHful est "the play lousy", a-t-elle écrit) a reHré au moins 37 minutes de Metropolis pour la sorHe américaine. En Allemagne, Alfred Hugenberg, industriel et magnat de la presse qui avait racheté UFA, s'est aVaqué au sous-texte poliHque supposé du film en coupant la copie originale. Futur membre du premier cabinet d'Adolf Hitler, Hugenberg voulait purger UFA des "républicains, juifs et internaHonalistes" du studio. Après la prise du pouvoir par les nazis, Metropolis a été encore plus coupé, jusqu'à 91 minutes. CeVe coupe était la version la plus couramment vue avant les années 1980 (bien que les notes préservées de la censure aient aidé à sa reconstrucHon éventuelle).

De l'avis général, les coupes n'ont pas aidé l’accueil du film à l'époque. Les criHques, comme nous l'avons menHonné, étaient plutôt sévères. Pourtant, nombre de criHques qui ont fusHgé Lang et von Harbou ont eu un respect réHcent pour les images éblouissantes du film. Le criHque Thomas Elsaesser rapporte que le criHque du journal français Les Annales a aVaqué la "lourdeur" du film, sa "prétenHon" et son "insurpassable stupidité", tout en trouvant Lang "capable d'images et d'une imaginaHon extraordinaires". De même, le cinéaste Luis Buñuel a criHqué le film pour son "romanHsme éculé" trivial, prétenHeux (encore) et pédant. Il pensait également qu'il pouvait "nous submerger comme le plus merveilleux livre d'images." [4]

Mais Lang ne s'est pas contenté d'habiller ses décors de néons et de chrome. L'un des secrets de la pérennité du film, étrangement, est dû au peu de "technologie du futur" à l'écran. À l'excepHon (très notable) du Maschinenmensch, la quasi-totalité de la technologie de Metropolis est du matériel vintage des années 1920. Fredersen et Rotwang marchent dans les catacombes guidés par de peHtes lampes de poche. Le sinistre sbire de Fredersen, The Thin Man, sort un téléphone d'un Hroir de la banqueVe arrière d'une voiture. C'était probablement un truc fou dans les années 1920, mais le temps a permis de le rendre réel. Sinon il y a très peu

d'autres avancées futuristes dans Metropolis. Les voitures sont des modèles Ts. Les biplans vrombissent dans les couloirs d'acier de la ville. Les tractopelles ressemblent à des tractopelles. Personne ne porte de chapeau en papier d'aluminium, d'uniforme réfléchissant ou de pistolet laser.

Les criHques affirmaient que Metropolis "prétendait parler du futur" sans faire de prédicHons définiHves, écrit Elsaesser. Cependant, rien ne vieillit plus vite que les "futurs imaginés" qui ne se produisent jamais. Les spectateurs modernes acceptent probablement mieux les biplans et la mode des années 1920 et imaginent le reste qu'ils ne le feraient avec des combinaisons spaHales kitsch et des voitures à réacHon profilées d'un avenir qui n'est jamais venu. L'une des raisons pour lesquelles le film est si moderne cent ans après sa réalisaHon est que l'on a l'impression de pouvoir toucher Metropolis. La ville et ses décors sont solides, comme si on pouvait les graVer sans que le carton ne s'effondre ou que le film ne se décolle.

Beaucoup vont maintenant dans la Cité des Morts

Même sous une forme tronquée, Metropolis a conHnué à inspirer des généraHons de cinéastes et d'arHstes, mais surtout de musiciens. Beaucoup ont regardé le film en silence ou avec un accompagnement musical sans rapport. Une parHHon originale a été écrite, mais la plupart des gens ne l'ont jamais entendue, car elle n'aurait pas été compaHble avec le film censuré. Elle n'a jamais été jouée après la première et n'a été enregistrée que plus de 70 ans plus tard.

Metropolis n'était pas tout à fait une oeuvre vierge, mais c'était souvent une oeuvre musicale vierge. Les arHstes ont commencé à se demander comment ceVe ville du futur pourrait raisonner.

KraÄwerk , probablement le groupe de musique électronique le plus influent de l'histoire, n'a jamais caché l'influence de Metropolis sur sa musique et son esthéHque. "Nous avons été très influencés par les films muets futuristes de Fritz Lang", a déclaré Ralf HüVer de KraÄwerk. "Nous avons le senHment d'être les fils de ce type de cinéma de science-ficHon. Nous sommes le groupe de Metropolis. Dans les années 20, les gens pensaient à la technologie du futur dans les domaines de la physique, du cinéma, de la radio, de la chimie, des transports de masse... tout sauf la musique. Nous pensons que notre musique est une conHnuaHon de ce futurisme précoce. Lorsque vous allez voir Star Wars, avec tous ses gadgets de science-ficHon, nous sommes gênés d'écouter la musique... des cordes du 19ème siècle ! CeVe musique pour ce

film ! ? Historiquement, nous pensons que s'il y a jamais eu un groupe de musique à Metropolis, peut-être que KraÄwerk aurait été ce groupe." [5]

KraÄwerk n'a jamais réalisé de bande originale pour Metropolis (bien qu'on leur ait demandé une fois d'en créer une). [Le groupe a cependant fait référence à plusieurs des concepts du film sur son album de 1978 Die Mensch-Maschine et plus exactement sur le troisième morceau de l'album, "Metropolis".

La restauraHon du film avec la musique sont arrivées sur le montage du film de 1984 de Giorgio Moroder. Le producteur italien a travaillé avec des historiens et des experts du cinéma pour sorHr une nouvelle version de 83 minutes de Metropolis, accompagnée d'une bande-son comprenant dix chansons écrites et produites par Moroder et interprétées par des stars de la radio rock des années 80, de Freddie Mercury à Pat Benatar et Billy Squier. Membre fondateur de Kluster/Cluster et d'Harmonia, Dieter Moebius a également composé une bande originale remarquable pour Metropolis, publiée à Htre posthume sous le Htre Musik für Metropolis en 2017.

Les différents efforts de reconstrucHon ont conféré à Metropolis un étrange dynamisme à parHr de 1980, surtout pour un film muet. C'était une œuvre d'art en constant renouvellement - et à chaque modificaHon, le film s'améliorait. De nouvelles restauraHons ont suivi celle de Moroder, avec des sorHes en 1987 et 2001. En 2010, The Complete Metropolis est sorH, basé sur une copie de sécurité redécouverte de l'original de Lang, avec 25 minutes d'images inédites en 80 ans.

Jeff Mills a publié sa première bande originale pour Metropolis en 2000. Louant le "message intemporel de solidarité" du film, Mills a déclaré que son objecHf était de "réintroduire et d'éduquer les théories et l'idéologie" de Metropolis auprès des jeunes à la fin d'un siècle et au début d'un nouveau.

Mills a écrit une deuxième bande originale pour Metropolis en 2010. Voici la troisième. Il ne s'agit pas d'ébauches d'un même travail en cours, mais de composiHons enHèrement disHnctes, avec une musique originale, et chacune écrite d'un point de vue différent et unique. La bande originale de 2000 a été réalisée du point de vue d'un spectateur regardant l'écran. La bande originale de 2010 a été réalisée du point de vue des personnages du film regardant les spectateurs regardant l'écran. La bande originale de 2022 se place du point de vue des machines et de la technologie de Metropolis et est composée comme une "bande originale électronique symphonique", jouée par un orchestre de machines sous la direcHon d'un chef d'orchestre.

Après "les deux dernières versions précédentes réalisées en 1999 et en 2010, j'ai pensé qu'il était temps de revisiter le film, car tant de choses avaient changé dans le monde et avec les gens (en général). CeVe nouvelle bande-son est plus émoHonnelle et plus profonde".

Mills a interprété les parHHons à de nombreuses reprises au fil des ans, "des grands auditoriums aux églises en passant par des projecHons sur des portes de garage. Mais à chaque projecHon, on comprend toujours qu'il est important de montrer ce film au public. Il ne s'agit pas seulement d'un film - il s'agit plutôt de leçons sur l'esprit humain que chacun d'entre nous devrait se rappeler. »

Que personne ne reste en arrière

Chaque généraHon croit probablement que le monde et le message de Metropolis sont plus perHnents pour nous et notre époque, que ceux qui nous ont précédés. J'imagine que ce sera toujours le cas. Comme tous les grands mythes, l'histoire de Metropolis sera sans cesse réinterprétée, réadaptée pour tenir compte des nouvelles réalités.

De même, les thèmes les plus généraux de Metropolis seraient probablement aussi significaHfs pour les gens d'hier que d'aujourd'hui - pour un ouvrier égypHen fabriquant les monuments funéraires de son dieu vivant, pour le fermier haïHen poussé par la pauvreté à se déraciner pour Cité Soleil, pour la femme de ménage dormant dans sa voiture après avoir neVoyé les maisons et les bureaux de la nouvelle élite de la Silicon Valley.

Metropolis tend un miroir sombre à l'Amérique de 2023. Pour beaucoup de gens dans ce pays, la pandémie a été leur première rencontre avec un système explicitement basé sur les classes, celui-ci divisé entre les "essenHels" et les "non-essenHels". (Au printemps 2020, j'ai souvent regardé par la fenêtre les tours modernes érigées pendant le boom immobilier des années 2010 dans toute l'Amérique - des graVe-ciel de verre et d'acier comme le "voile verHcal, chatoyant, presque sans poids, un Hssu luxueux suspendu au ciel sombre pour éblouir, distraire et hypnoHser" de Fritz Lang. Chaque lumière était allumée, chaque âme "non essenHelle" était en sécurité chez elle. Dans les rues désertes, des livreurs pédalent, des boîtes carrées doublées d'aluminium aVachées à leur dos, des "travailleurs essenHels" apportant de la nourriture, du papier toileVe et de l'alcool aux portes des "non-essenHels". Ces images désolantes de l'Amérique en état d'urgence étaient parmi les visions les plus "métropolitaines" que j'aie jamais vues - jusqu'à ce que, quelques mois plus tard, des vagues d'émeuHers s'abaVent sur les mêmes tours, pillant les magasins haut de gamme au niveau de la rue, mais laissant intacts les occupants des tours situées au-dessus. Le lendemain, ceVe marée humaine s'est reHrée, mais les ponts sur la rivière Chicago ont été levés, les métros souterrains bloqués pour les empêcher de revenir des catacombes.

Pour ces raisons, lorsque j'ai regardé la version restaurée Metropolis de 2010, j'ai été fasciné par le personnage de Josaphat, l'assistant de Fredersen. Fredersen licencie Josaphat (mot hébreu signifiant "Yahvé a jugé") pour ne pas l'avoir informé de l'explosion de l'usine "Moloch" avant que Freder ne lui en parle.

Josaphat manque de se tuer à cause de cela, mais pas par honte. Comme Freder averHt son père, la seule mobilité sociale à Metropolis va vers le bas. Perdre son emploi au sein de l'élite signifie que Josaphat devra désormais descendre dans les souterrains de la cité ouvrière, une perspecHve considérée comme un sort pire que la mort.

Antonio García Maránez caractérise une parHe de la société américaine de 2018 comme légèrement plus avancée que celle de Metropolis : il la divise en quatre castes plutôt qu'en deux, mais chaque classe inférieure partage la terreur de Josaphat de descendre dans l'échelle

sociale. Ceux qui se situent en dessous des élites ne peuvent que rêver de pouvoir "conduire/ acheter/bricoler suffisamment pour s'élever" vers une classe supérieure. En praHque, cela n'arrive jamais. [Avec l'explosion du nombre de personnes employées mais sans abri dans les villes d'Europe et d'Amérique, on peut se demander si nos dirigeants n'ont même pas la misérable humanité de Joh Fredersen au début de Metropolis, qui donnait au moins à ses ouvriers leur propre ville pour y dormir. Peut-être que Fredersen était simplement plus intelligent.

Plus tard, lorsque le Maschinenmensch incite les ouvriers de Metropolis à se révolter, ils laissent derrière eux leurs enfants et dansent ensuite pour célébrer alors qu'ils se noient dans la ville sous leurs pieds. L'insurrecHon du 6 janvier était une séance de jeu de rôle en direct de ceVe scène centrale du film (sans la jusHficaHon sous-jacente des travailleurs), alors que Donald Trump incitait ses parHsans à détruire une autre "métropole". Ce désir de vengeance a conduit à une orgie de violence et, comme le film le prédisait, à l'autodestrucHon des émeuHers eux- mêmes, trompés ou séduits par les ouHls du Rotwang brûlé par le soleil de notre siècle. Lang et von Harbou nous ont prévenus que les mains sans le cœur sont tout aussi dangereuses que la tête sans le cœur - et tout aussi vicieuses.

Ces scènes du monde moderne montrent bien plus que la vague ressemblance entre l'art et la vie. Le message de Lang et von Harbou est toujours aussi perHnent aujourd'hui qu'il l'était en 1927 : toutes ces construcHons - ces machines - ont été faites par des hommes, et sont toujours contrôlées par des hommes, pour dominer leurs semblables. Un système économique vicieux n'est pas la créaHon des dieux ou de la nature, mais un ouHl créé par des personnes pour exploiter d'autres personnes. C'est une machine que vous ne pouvez pas voir, mais c'est une machine tout comme les usines et les turbines qui dévorent la chair humaine.

Dans le monde du 21e siècle, nous craignons toujours que les machines prennent le dessus, que les robots gagnent. Mais si les robots prennent le pouvoir, la leçon de Metropolis est que ce ne sont que des humains qui sont derrière eux, et que les mêmes ouHls uHlisés pour opprimer l'humanité peuvent aussi être uHlisés pour la libérer.

CeVe peur n'est pas prête de disparaître, mais les leçons de Metropolis non plus. Dans cent ans

- deux cents ans après la créaHon de Metropolis - nos machines seront plus omniprésentes que jamais. D'ores et déjà, de peHtes machines se connectent à des machines plus grandes pour effectuer des tâches subalternes en notre nom, une tendance qui ne fera que s'accentuer à mesure que chacune deviendra exponenellement plus puissante et efficace.

Pourtant, l'omniprésence s'accompagne d'invisibilité, et ceVe invisibilité engendre une nouvelle forme de crainte. De même que peu de gens verront un jour un serveur Google, les machines du futur seront de plus en plus invisibles et tellement intégrées à la vie quoHdienne qu'il sera difficile de les reconnaître comme les descendants du Moloch industriel de Freder dans les années 1920. Nous craignons ce que nous ne pouvons pas voir - la "terreur de la nuit", la "peste qui rôde dans l'obscurité" - plus que ce que nous pouvons. Et nous craindrons toujours que ces

ouHls se nourrissent de nos vies et de nos esprits, que leurs algorithmes se déchaînent pour manipuler la réalité autour de nous, et nous avec. Peut-être verrons-nous enfin la machine échapper au contrôle de l'humanité, mais il est plus probable qu'elle fera toujours parHe d'une collecHon d'ouHls pouvant être exploités par leurs créateurs - les dirigeants d'une future Metropolis - pour monter les humains les uns contre les autres ; uHlisés pour lancer une néo- élite encore plus loin dans le ciel que dans les graVe-ciel de ManhaVan ou de Metropolis, explorant les systèmes solaires et gardant les autres sous terre, "là où ils doivent être".

C'est là la véritable source de la puissance du film. Metropolis nous invite à prendre un aperçu de notre monde, à le confronter à sa propre dystopie cauchemardesque et à uHliser un stylo rouge pour entourer tout ce qui est idenHque. Il est tentant de croire, à parHr des résultats de ce test, que le monde se dirige irrévocablement vers la folie de Metropolis.

Tentant, mais faux. Lang lui-même fournit une réponse à cela, le message primordial de Metropolis et un secret qui peut abaVre le pire de la société et de la technologie, c'est-à-dire le pire de l'homme : la solidarité. Ou dit autrement :

"Regarde ! Ce sont vos frères."

[1] McGilligan, Patrick. Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast (St. Martin's Griffin Press, 1997).

[2] Kracauer, Siegfried. From Caligari to Hitler (North Rivers, 1947).

[3] “The 100 Greatest Films of All Time.” (Sight and Sound, Updated June 28, 2021)

[4] Elsaesser, Thomas. Metropolis. (BFI Publishing, 2000).

[5] Barr, Tim. Kraftwerk: From Dusseldorf to the Future (With Love) (Ebury Press, 1999).

[6] Schütte, Uwe. Kraftwerk (Penguin Books, 2021).

[7] Garcia Martínez, Antonio. "How Silicon Valley Fuels an Informal Caste System." (Wired, July 9 2018).

Metropolis

by: Terry Matthew

En defensa de las máquinas: Una nueva mirada al mundo futuro de Metrópolis

Retenido toda la noche mientras las autoridades revisaban sus papeles, Fritz Lang subió a la cubierta de un barco amarrado en el puerto de Nueva York y contempló el horizonte con asombro. Sus problemas de visado no eran motivo de alarma; ni siquiera era la primera vez que el director era retenido como "extranjero enemigo". Le liberarían y le permitirían desembarcar del SS Deutschland cuando las cosas se arreglaran al día siguiente.

Pero fue allí -con los pies en un barco llamado "Alemania" y la mirada fija en el horizonte de Manhattan- donde Lang tuvo una visión para su próxima película, un tipo de película que nunca se había hecho antes.

"Vi una calle iluminada como a plena luz del día por luces de neón", diría más tarde. "Encima de ellas [había] anuncios luminosos de gran tamaño, girando, encendiéndose y apagándose intermitentemente, en espiral... algo que era completamente nuevo y casi de cuento de hadas para un europeo en aquellos días...".

"Los edificios parecían un velo vertical, resplandeciente, casi ingrávido, una lujosa tela colgada del cielo oscuro para deslumbrar, distraer e hipnotizar. De noche, la ciudad no daba la impresión de estar viva: vivía como vivían las ilusiones." [1]

"Allí", le diría Lang más tarde al director Peter Bogdanovich, "concebí Metrópolis".

Esta historia no es del todo cierta. Hay muchas pruebas de que los preparativos de Metrópolis estaban en marcha -incluido el guión escrito por su entonces esposa Thea von Harbou- antes de que Lang y el productor Erich Pommer, del gigante de los estudios alemanes UFA, embarcaran en el SS Deutschland en 1924. Pero Lang, un maestro de la semiótica, reconocía un buen símbolo cuando lo veía. Esta fábula -que recordaba su película pionera como alemana e internacional a la vez- se convirtió en el mito fundacional de la realización de Metrópolis.

Sin embargo, no cabe duda de que las catedrales eléctricas de Nueva York inspiraron realmente los impactantes efectos visuales de Metrópolis, al igual que los estadounidenses que conoció cuando los dos alemanes recorrieron la ciudad al día siguiente. Hacía "un calor espantoso", recordaba Lang, una vorágine de humanidad como un "cráter de fuerzas humanas ciegas y confusas, empujándose y machacándose unas a otras".

Se han escrito muchos libros sobre lo que inspiró a Lang y Metrópolis, las referencias al arte visual, las pinturas y las máscaras tribales que inspiraron el rostro del Maschinenmensch, el icónico androide de la película. Pero, ¿por qué sigue inspirándonos Metrópolis? ¿Qué tiene esta película muda, su mensaje y sus temas, que ha movido a algunos de nuestros músicos más célebres a ponerle música? ¿Y por qué tantos compositores de música electrónica en particular están fascinados por una película sobre el futuro que tiene más de 100 años?

Metrópolis fue tachada de "cuento de hadas" por más de un crítico en su día. No fue un éxito popular cuando se estrenó, y de todos modos habría sido difícil que la película recuperara su gigantesco presupuesto. Algunos criticaron lo que identificaron como un mensaje "comunista" en su argumento, una advertencia de lo que podría ocurrir cuando los trabajadores hundidos en la miseria se sublevaran contra la clase dominante. El sociólogo, escritor y crítico alemán Siegfried Kracauer argumentó que captaba los ideales protofascistas que se estaban fraguando bajo el firmamento de la sociedad alemana de la época[2] Los críticos dramáticos tacharon la historia de simple, "pueril", casi vergonzosa.

Los ejecutivos del cine la consideraron una catástrofe y cortaron más de una cuarta parte de la película tras su estreno en Alemania. Los nazis recortaron aún más. Considerada la película más cara de la historia, todo el mundo sabía en qué se había equivocado Lang.

Pero a medida que Metrópolis se fue reconstruyendo a lo largo del siglo pasado -a partir de copias dispersas y de las notas de un censor nazi-, se hizo evidente el alcance de la visión de Fritz Lang. Metrópolis ha sido revalorizada por la crítica y hoy se considera una de las mejores películas de la historia: la influyente encuesta de Sight and Sound la situó por última vez en el puesto 35, empatada con Psicosis, de Alfred Hitchcock[3]. [3] Y en muchos sentidos, son estos "defectos" señalados por los críticos en 1927 los que confieren a la película su poder para abrirse paso entre un público que, de otro modo, nunca vería una película muda. En Metrópolis, Lang y von Harbou construyen una nueva mitología en la cáscara de la antigua, una mitología que puede ser contada de forma sencilla y comprendida por los niños, y también interpretada, analizada y rumiada por eruditos y sabios en busca de sentido.

¿Y si un día los de las profundidades se alzan contra ti?

Metrópolis tiene lugar en una ciudad de nombre homónimo en algún momento del futuro (los años 2000, 2026 y 3000 han sido mencionados por diversas entidades relacionadas con la película a lo largo de los años). La sociedad está muy estratificada: las élites de la ciudad llevan una vida decadente en lo alto de gigantescos rascacielos art déco. Los trabajadores, por su parte, caminan robotizados desde las fábricas hasta sus casas en una ciudad subterránea. La salud, el aire fresco y, al parecer, incluso la felicidad son privilegio de una élite bien nacida.

Freder, hijo del gobernante de Metrópolis, está a punto de hacer lo que quiere con una cortesana elegida a dedo cuando una mujer, María, irrumpe en el Jardín Eterno con un puñado de niños mendicantes procedentes del subsuelo. Sus ojos hundidos miran a su alrededor mientras ella hace gestos a la gente glamurosa. "Mirad", dice a los niños, "estos son vuestros hermanos".

Estas son las palabras que encienden la trama e impulsan a Metrópolis hacia la destrucción y la redención. Freder, conmocionado, va tras María y es testigo de un accidente industrial en el que mueren varios trabajadores. Tras el accidente, alucina con la gigantesca fábrica transformada en Moloch, dios del sacrificio humano, que devora a los trabajadores como "alimento vivo para las máquinas".

Freder corre a contarle a su padre, Joh Fredersen, lo sucedido. Fredersen no lo sabía, y Freder es lo bastante ingenuo como para creer que a su padre podría importarle como tragedia humana y no financiera.

Esta escena contiene algunos de los diálogos más importantes de Metrópolis. El público de 1927 conocía sin duda a este tipo de industrial villano, así como los peligros de muerte o desfiguración del empleo en las fábricas y las minas.

"¿Y si un día los de las profundidades se sublevan contra ti?". le pregunta Freder a su padre. Freder es ese joven ilimitadamente optimista que no puede imaginar que estas condiciones existen por designio, porque es más rentable tratar a los trabajadores como herramientas desechables, menos valiosas que las máquinas a las que sirven. Fredersen se limita a sonreír.

"¿Dónde está la gente, padre, cuyas manos construyeron tu ciudad?". pregunta Freder, en una pregunta que atraviesa décadas y pronto serán siglos de conflicto social. Uno casi puede imaginarse estas palabras pronunciadas de nuevo, en 2022, en relación con la lucha contra el racismo sistémico de los descendientes de esclavos africanos. ¿Dónde están las personas cuyos cuerpos se rompieron para construir nuestras ciudades?

Ninguno de nuestros líderes nos responde, pues no poseen la brutal franqueza del gobernante de Metrópolis. Él responde: "Donde pertenecen".

Muerte a las máquinas

Abandonando a su padre, Freder persigue a María utilizando un mapa encontrado con uno de los muertos, que le conduce bajo tierra hasta unas catacumbas situadas bajo la ciudad obrera. Allí, sobre un púlpito de cruces primitivas, María habla a los exhaustos trabajadores sobre un mesías venidero, un "mediador" que unirá las manos (los trabajadores) y la cabeza (la clase dominante) de la ciudad. Vuelve a contar la parábola de la Torre de Babel como una historia de lucha de clases: personas esclavizadas para construir un monumento a la humanidad que asciende como un dios, dedicado a la "humanidad", incluso mientras se les priva de la suya propia.

Del mismo modo, el Maschinenmensch es terrorista, pero sólo porque está en manos de terroristas; sólo hace lo que se le ordena. Llama a los trabajadores a rebelarse no atacando a la clase dominante de Metrópolis, sino exigiendo "¡Muerte a las máquinas!". Por las instrucciones de Rotwang, parece entender que atacar a un miembro de la clase dominante como Fredersen sólo llevaría a que otro, posiblemente peor pero sin duda no mejor, dirigiera Metrópolis. Atacar a las máquinas, sin embargo, aseguraría la destrucción de todos.

Enardecidos por el Maschinenmensch, los trabajadores abandonan a sus hijos para sembrar el caos en Metrópolis. Sólo más tarde se dan cuenta de que una de las máquinas que han "matado", la Máquina Corazón, es el sustento de sus hogares subterráneos. Mientras las aguas se precipitan y crecen destrozando la ciudad, María utiliza otra máquina -una campana gigante en la plaza de la ciudad- para un fin positivo, reuniendo a los niños abandonados para llevarlos a un lugar seguro.

Metrópolis no es la historia de una tecnología que escapa al control de los hombres. Se trata de una tecnología firmemente controlada por los hombres, hombres despiadados despojados de toda moralidad. Este es el significado del epigrama de la película -que el mediador entre la cabeza y las manos debe ser el corazón- y una de las razones por las que el mensaje de la película ha seguido perdurando. Nunca se ha tratado de derrocar a los robots o a las máquinas. Trata de las personas que los controlan, de nuestro sentido de la solidaridad y de cómo podemos recuperarlo.

Los trabajadores inclinan la cabeza. Son los mismos trabajadores pobres sobre los que Upton Sinclair escribió en La jungla, décadas antes de que se hiciera Metrópolis, que describía "la rotura de los corazones humanos por un sistema que explota el trabajo de hombres y mujeres".

Pero mientras los trabajadores practican su religión con María, los gobernantes de Metrópolis tienen su propio credo. Fredersen espía esta reunión junto a Rotwang, arquetipo del científico loco pero también una especie de mago al que Fredersen visita cuando sus expertos le fallan. Rotwang es también una conexión entre las dos castas de Metrópolis, pero no la utiliza para mediar entre ellas sino para llevar adelante sus planes de venganza. Rotwang ha construido una enorme escultura que conmemora el rostro de Hel, su amor perdido que le abandonó por Fredersen y dio a luz a Freder antes de morir. Ha construido un androide a su imagen: el Maschinenmensch o Persona-Máquina. Durante su construcción perdió una mano y la sustituyó por una prótesis mecánica cubierta por un guante negro. Fredersen quiere utilizar la Maschinenmensch para subvertir y provocar a los trabajadores con el fin de destruirlos. Rotwang planea utilizarlo para destruir la ciudad y, por tanto, a Fredersen. Es el único personaje humano de la película que es en parte máquina, y ha construido otra máquina para destruir las máquinas.